My younger sister, Lauren, is the smartest person I know. She's a lawyer and land use expert, a trivia champ with the best deductive reasoning skills of anyone I've ever met and I hate watching Jeopardy with her. My mom loved to tell a story where she was about 4 years old and confidently prefaced a question with "when you grow small..." based on the presumption that if Lauren herself was small and growing larger, certainly the large people must be growing the other direction. It makes perfect sense, right?

Our kids are so smart it's easy to forget that they may be missing key bits of information. It's easy to have full conversations based on the assumption that they understand the foundational aspects of stuff like, y'know, the unrelenting forward march of time. Basic stuff. In giving our kids the skills to thrive, we impart logic and knowledge and social structures. We enforce manners and assess both their fine and gross motor skills. While we occasionally point out snow on the mountains to the East here in Southern California, our acknowledgement of the natural cycles around us seems to have been crowded out by the pre-academic studies of colors, shapes and ABCs.

I'm lucky enough to live below the Topa Topa mountains and after the first real raindump of the season, my husband offhandedly mentioned "we won't see brown mountains for at least another 5 months" and that casual observation which seems obvious in hindsight was more like a magic power, a deep ancient knowledge. He knows cycles. I fell in love with Danny on a full moon nature hike when he led me (and 25 other adults) in the titular hills of Beverly Hills. He is a font of botanical trivia and latin tree names but, more than that, years working in nature trained him to be curious, look for clues and make connections. It's a talent and a skill.

We can point out leaves that turn orange and then fall from the tree, and then point out the new growth in the spring. We can find the line in the sand showing the high tide point and talk about the way the waves move closer and further from shore. We can take our shoes off and feel the thick grass on our feet after a heavy rainstorm and reminisce about how crispy it was just a few months ago. We can watch the moon grow from a sliver to a half to a big round circle and then howl, howl, howl (as I said before, we're a loud bunch). We can share pictures of the older people in our lives -- grandparents, teachers, parents and even familiar faces on TV -- when they were young. The goal is not to explain, just to notice.

Embracing the predictability of the cycles around us and pointing out what we observe to the tiny scientists in our care is a way of laying a foundation for conversations about death further down the line.

DO:

There are ways to bring the natural cycles around us into focus for our kids, but we adults need to tune in first. Pick something you see everyday -- the moon, a flowering bush in your yard, the mountains in the distance or even just the shadow cast by a telephone pole -- and watch it. Just look at it often and notice how it is changing over time. Of course the moon runs on predictable 28-day cycles and the shadow of a telephone pole will make a consistent path day after day. The flowering bush may change incrementally or may make dramatic shifts, so look for the rhythm. Seems like you're not doing much, but you're training your brain to find the pattern and uncover the unexpected.

READ:

The Digger and the Flower by Richard Kuefler (2018)

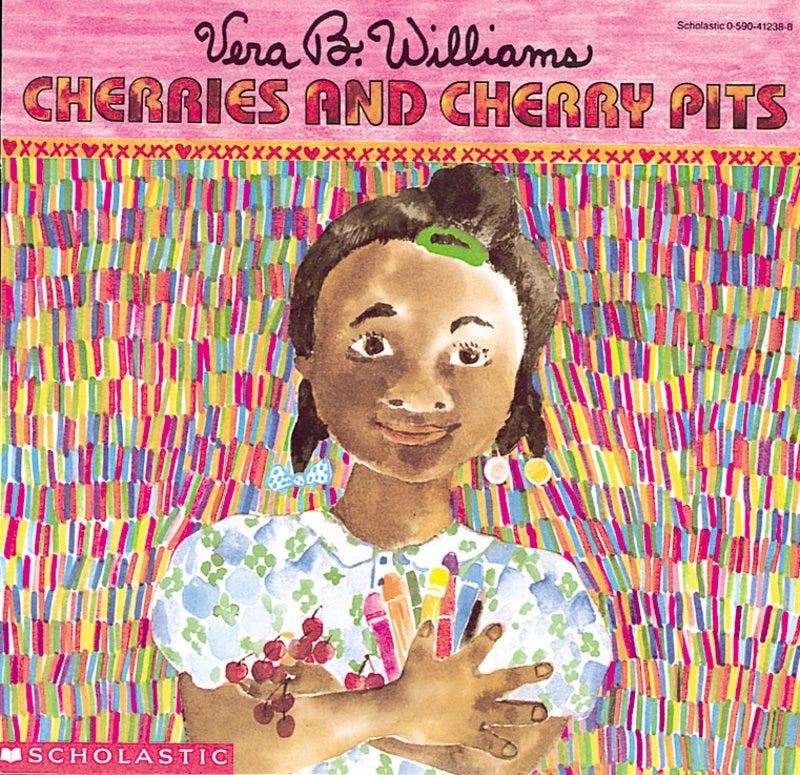

Cherries and Cherry Pits by Vera B. Williams (1991)

Each of these books wrestles with loss and power. Bidemmi and the Digger find ways to take control and manage their experience of loss. While The Digger and the Flower more closely grapples with death, the comforting themes of cycles and predictability are found in both.

"He drove to a place no big truck had ever been. There, Digger stopped. He dug and scooped and tucked the seeds into the warm earth."

“Our yard is a junky old yard. It has this stump where there used to be a tree. But that tree died and they came and cut it down and took it away. Then I poke pits in the ground all over the place. I know if I plant enough of them at least one will grow.”